|

Book Review The Death and Life of the Great Lakes By Dan Egan 384 pp. W.W. Norton & Company, 2017  In 2012, journalist Dan Egan, his wife, and their four children moved to New York City for a year so he could pursue a fellowship at Columbia University. Part of the program was to write a book proposal. "There were sixteen students in the classroom," he recalled several years later. "I don't think any of them were from the Great Lakes Basin. There was a lot of discussion about what we were pursuing, and every time I started telling Great Lakes stories, they just became rapt. It was really eye-opening to me, because of what we take for granted here [in the midwest]—the story of the Great Lakes." By that point he had been reporting on the Great Lakes for nearly a decade for the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel. He imagined his various stories, on everything from invasive species to algal blooms, and "they seemed to stack up like chapters." He hadn't planned to actually write the book—just fulfill his course requirement—but he got good feedback from his peers and professors. "Basically," Egan said, his professor told him he would be "crazy not to harvest a decade's worth of reporting and put it all between two covers. It was good advice." A lifetime of fishing on the lakes—and fifteen years reporting on the lakes—makes Egan a knowledgeable and passionate guide to a wondrous and complex fresh-water system. He grew up in Green Bay, Wisconsin, and lives in Milwaukee. As a child he vacationed with his grandparents on the Door Peninsula, swimming in the clean waters north of industrialized Green Bay. His expertise runs far beyond childhood fancy, however. His work on the Great Lakes has made him a two-time finalist for the Pulitzer Prize in explanatory reporting, first in 2010 for writing on how invasive species have disrupted the ecosystem and economy of the Great Lakes, and again in 2013 for reporting on efforts to keep new invasive species—especially Asian carp—out of the lakes. Both of these topics make up the bulk of his book. Egan's knowledge of the subject is apparent in the clarity with which he explains the various environmental, economic, social, political, and historic factors at play. Just how big are the Great Lakes anyway? (Data from Wikipedia and Michigan State University)

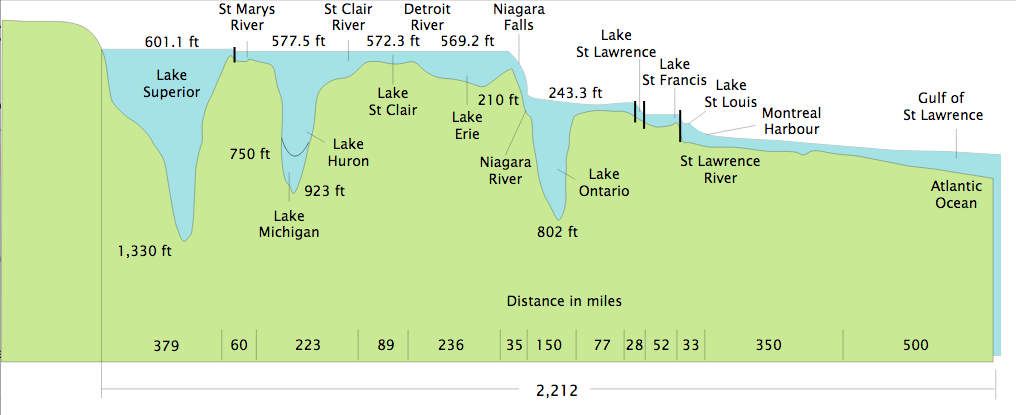

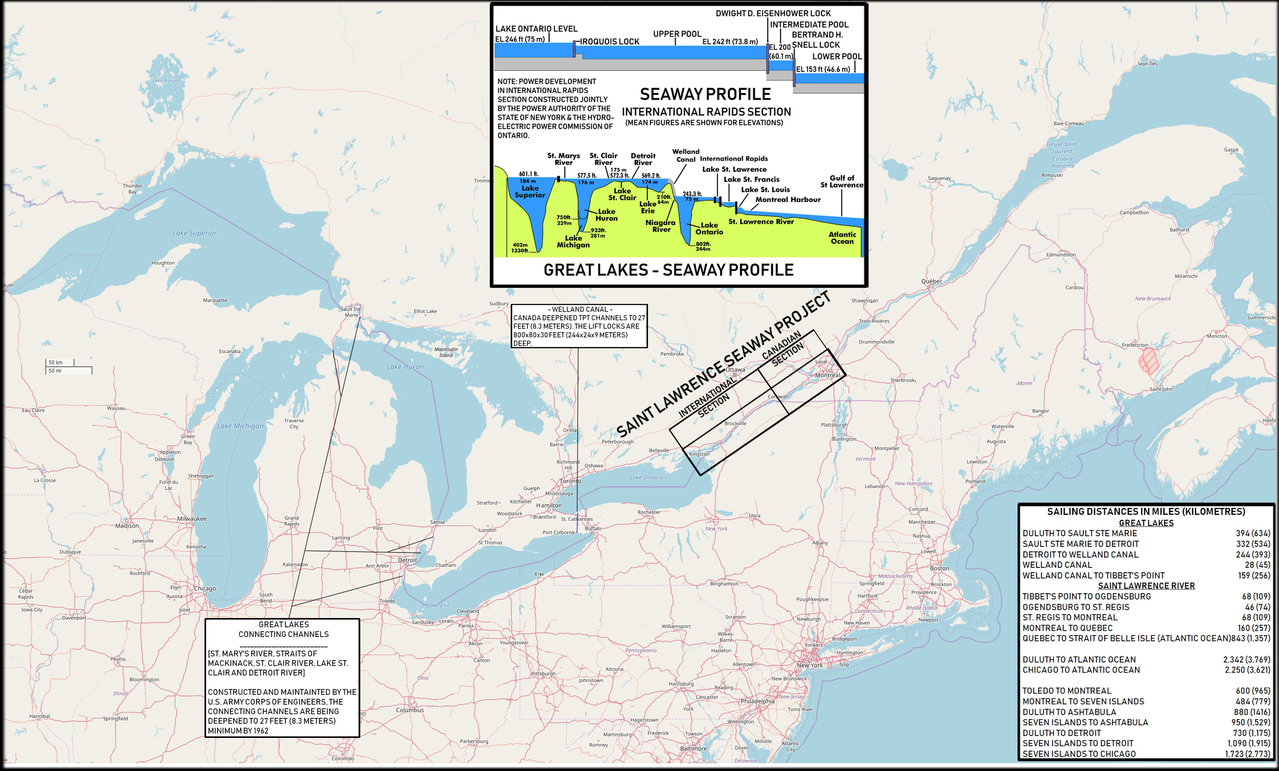

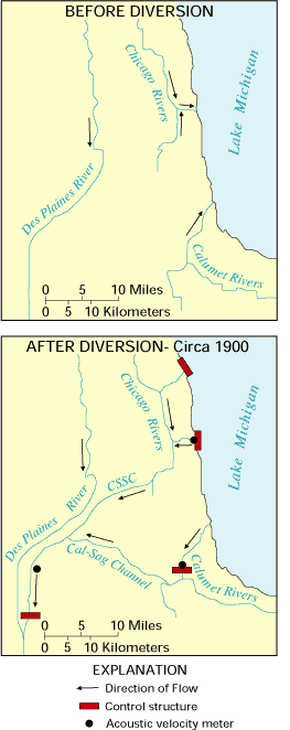

The first two sections of the book—called "The Front Door" and "The Back Door"—focus on the threats of invasive species to (and from) the lakes. According to Egan, "The front door/back door theme really did help organize the issues in my mind," allowing him to separate the wave after wave of invasive species that followed the construction of the St. Lawrence Seaway (the front door) from the threat of invasives entering the lakes from the Mississippi River through the Chicago Sanitary and Ship Canal (the back door). While the first two sections focus mainly on the lakes' biota, the final chapters are about water, a non-trivial topic for a book on lakes. The Great Lakes formed at the end of the last glacial period, around 14,000 years ago. For their entire pre-industrial existence they were isolated from the rest of the world by two natural boundaries: Niagara Falls, which protected the four upper lakes from the Atlantic Ocean (that is, Lakes Erie, Huron, Michigan, and Superior—Lake Ontario is downstream from Niagara but was itself opened to the Atlantic by the 1825 completion of the Erie Canal), and a continental divide along the lakes' southern shores, which protected the Great Lakes from the Mississippi River watershed. But beginning in the late 19th century, several large-scale projects were initiated to circumvent these natural barriers and open up the Great Lakes to the rest of the world. The first of these was the St. Lawrence Seaway, completed in 1959 and described by Walter Cronkite as the "greatest engineering feat of our time" (Egan p. 3). The purpose of the St. Lawrence Seaway was to allow oceangoing cargo ships to enter the Great Lakes directly from the Atlantic. It was supposed to connect middle American ports such as Cleveland, Chicago, Detroit, and Duluth to the rest of the world. But despite the fanfare, the project largely failed because the locks meant to transport the ships up the canal and through the lakes were built far too narrow for modern cargo ships. The true calamity however was much worse than a mediocre economic impact. Instead of global cargo, the seaway brought to the Great Lakes an "ecological catastrophe unlike any this continent has seen" (Egan p. 4). That is, wave after wave of invasive species that hitched a ride on and in the ships coming up the seaway. What followed was a tragicomedy (mostly a tragedy, really) of accidental yet foreseeable environmental calamities and bumbling human efforts to fix things. First came the lampreys, and then the alewives, and the Pacific salmon which were introduced into the lakes to prey on the alewives. Then, beginning in the late 1980s, came the most famous invasive species of all, the quagga and zebra mussels which arrived in the lakes in the ballast waters of ocean-going cargo ships.  The construction of the Chicago Sanitary and Ship Canal (CSSC) connected the Great Lakes to the Mississippi River watershed. The construction of the Chicago Sanitary and Ship Canal (CSSC) connected the Great Lakes to the Mississippi River watershed. How could it possibly get worse, one might think while reading these pages, than an infestation of bivalves, the extent of which is truly mind-boggling? How could it possibly get worse than an invasive species that siphons off the base of the food web before any other lake-dwelling creature has a chance? How could it possibly get worse than a hardy mollusk that encrusts on all hard surfaces, including pipes, dams, docks, and boats? "It would be foolish," says Egan, "to think things could never get worse." In fact, that is the overriding theme of Egan's second section, "The Back door." During the mid-1800s, Chicago was growing quickly. The city's population swelled from less than 5,000 in 1840 to more than 100,000 in ten years. The city's sewage was dumped into the Chicago River, which at the time flowed back into Lake Michigan, bringing with it a slew of waterborne diseases right into the drinking water of Chicagoans. A nice and tidy disease-delivery system that, not surprisingly, was unpopular with city dwellers. The solution, opened in 1900, was a 28-mile-long canal that connected the Chicago River to the Des Plaines River and effectively reversed the flow of the rivers out of Lake Michigan instead of into it. It also connected Lake Michigan—and the rest of the Great Lakes—to the Mississippi River system. "This canal," Egan explains, "removed the last plug in a continental navigation network that finally allowed for goods and people to float up the Erie Canal from the East Coast, across the Great Lakes and then down the Mississippi River and into the Gulf of Mexico" (Egan p. 152). It also removed the last protective barrier between the Great Lakes and any potential threat from—and to—the rest of the continent. "The problems," Egan says, "started with a box. A box full of fish." File this under plans gone awry: In a 1963 effort to control aquatic weeds in a non-toxic manner, the federal government imported carp from Malaysia that were supposed to eat the weeds in a nice, friendly, fishy sort of way. Egan tells a riveting narrative of how one thing led to another, and then there was a federal breeding program, and then money dried up, and then… the fish were just set free. According to Egan, "this was a blunder of the highest order." He continued, "the problem is bighead and silver carp don't just invade ecosystems. They conquer them. They don't gobble up their competition. They starve it out by stripping away the plankton upon which every other fish species directly or indirectly depends" (Egan p. 156-157). The carp have demolished native river fish species and disrupted recreational boating on Mississippi River tributaries. Viral videos of Asian carp show the fish leaping and flying out of the current, bludgeoning and bruising people attempting to water ski or enjoy a day on a boat. In fact, the hyperactive carp have themselves become sensation, although not in a good way. Since their release into the wild, Asian carp have steadily migrated northward and they now pose a very real threat to the Great Lakes. Only one electric barrier remains, protecting the Great Lakes from yet another invasive species, and there are concerns that the carp may have already breached this final blockade. Egan believes that invasive species are the biggest threat facing the Great Lakes: "Invasive species are often referred to as biological pollution. It is pollution, but it doesn't decay or disperse like traditional pollutants. We can't really get a handle on it because it breeds." Despite the clear threat posed by invasive species, Egan does not shy away from reminding us that there are other threats as well. He spends the final chapters of his book discussing agricultural run-off, toxic algal blooms, decreasing water levels, climate change, and water rights. But it’s not all doom and gloom. Throughout the book he introduces us to people working hard to contain the problems, offers potential solutions, and even gives us a few hopeful anecdotes of native species rebounding and pollution dwindling. His ultimate goal was to introduce the lakes—in all their troubled glory—to a nation of people who do not realize how important, how interesting, and how threatened they really are: "My biggest idea in writing this book was to give people a Great Lakes literacy. To not tell the whole history of the lakes, and not tell every issue facing the lakes, but just to have a survey of what I see as the important, critical issues facing them. If people become aware of what the problems are and what's causing them, hopefully that will spur them to demand fixes." In my case, he was successful. I opened this book knowing nothing about the lakes except that they are very large and near Chicago; I closed the book with a sense of wonder and fear that what I had just discovered might soon be lost. Dan Egan, The Death and Life of the Great Lakes (New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2017)

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

August 2020

Categories |

Proudly powered by Weebly