|

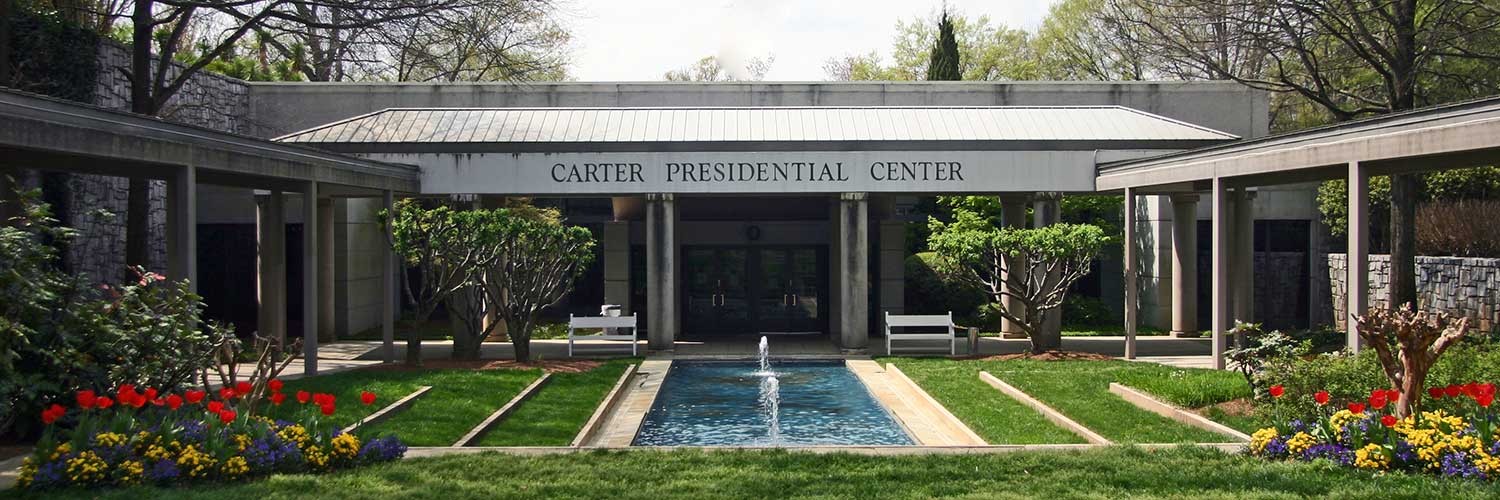

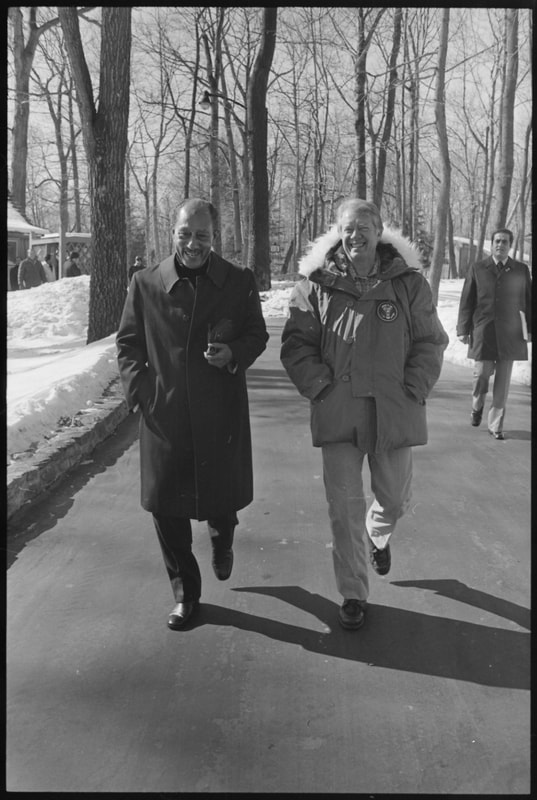

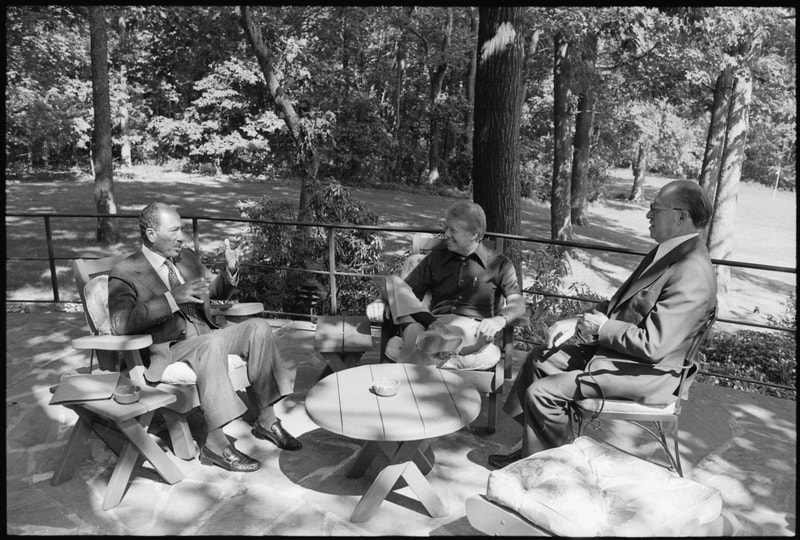

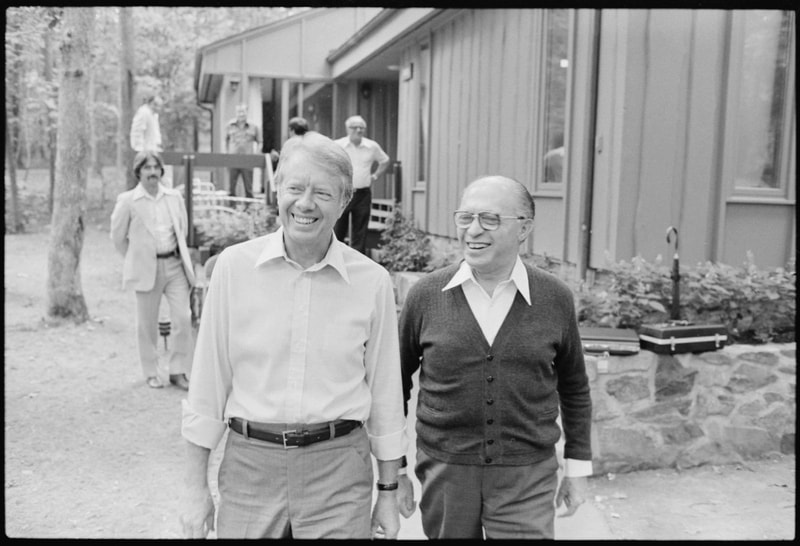

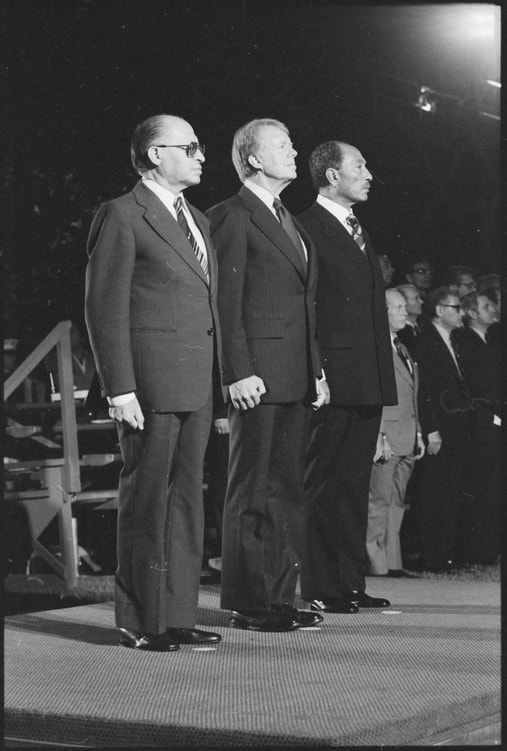

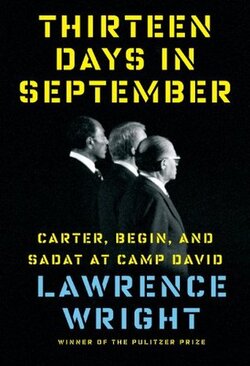

Thirteen Days in September: Carter, Begin, and Sadat at Camp David By Lawrence Wright 368 pp. Knopf, 2014 The Carter Presidential Library is only a few minutes from downtown Atlanta, yet feels a world away from the bustling metropolitan area. The museum is situated on thirty acres of manicured lawns, colorful flowerbeds and tree-lined walkways. There is a fountain, a duck pond, winding paths, and benches tucked under trees. I visited the museum in the summer of 2015, shortly after I finished reading Lawrence Wright’s Thirteen Days in September: Carter, Begin, and Sadat at Camp David. As you wander through the museum, you pass a series of exhibits on everything from the Panama Canal Treaty to the Carter White House’s diplomatic relationship with China. (If you can't make it to Atlanta, you can still take a virtual tour inside the Carter Presidential Museum.) And then, just past a sparkly silver dress of First Lady Rosalynn Carter’s, the blue carpet shifts to a hardwood floor, the passage narrows, and the ambient colors become bright and woodsy. The greens and browns dramatically contrast with a large blue Star of David that takes up much of the left wall. Across from it is the large outline of a rustic cabin. You have entered Camp David. Photos line the walls of the twisty narrow exhibit, showing the president and first lady with Israeli Prime Minister Menachem Begin, Egyptian President Anwar Sadat, their wives, and various aids and advisors—shaking hands, relaxing on a deck in wooden lawn chairs, playing chess, deep in though late at night, walking along wooded paths, and with feet up on coffee tables. They called it “cabin-to-cabin diplomacy.” Despite many obstacles, stand-stills, and disagreements, and several threats of failure, Jimmy Carter’s long-dreamed peace talks between Egypt and Israel succeeded. Although they obviously did not solve all the region’s problems, the tenuous peace signed on 17 September 1978 still holds. It was the first agreement between Israel and an Arab state, and it resulted in Nobel Peace Prizes for Sadat and Begin (but not for Carter).  I was on a Carter high after visiting the museum, especially since I had recently heard Lawrence Wright give a talk about his book, Thirteen Days in September, at the Sun Valley Writers’ Conference. It was one of the better author talks I’ve attended, and even years later I remember bits clearly. Wright is best known for The Looming Tower: Al-Qaeda and the Road to 9/11, for which he won the 2007 Pulitzer Prize for General Nonfiction. His most recent book, The End of October (a shockingly on-point novel about a global pandemic), was published in April 2020. At the talk I attended in 2015, Wright said Thirteen Days in September was the most structured of all his writing, and that he had been especially influenced by John McPhee. “If you want to read a master of structure,” he said, “go to The New Yorker’s website and look for every article by John McPhee.” So I did. There are approximately 27 thousand of them. I read two. John McPhee is, without a doubt, a master of structure, but I find his prose tortuous. A quick scan of Wright’s Table of Contents reveals thirteen chapters (titled “Day One,” “Day Two,” etc.). These chapters provide the framework for Wright’s narrative of the 1978 peace talks between Begin and Sadat, which were hosted at Camp David by President Carter. This story is the heart of the book, but Wright weaves in several other layers of narrative, described in the Author’s Note: “The reader will observe that there are three chronologies at work in this book. The thirteen days of the Camp David summit form the architecture of this account. Beneath that is a history of the modern Middle East as seen through the eyes of the remarkable men who were present at the negotiation and in many respects made that history. At bottom are the tectonic plates of the three religions as revealed in the stories of the Torah, the Bible, and the Quran” (Wright 2). The book therefore involves a lot of back-and-forth through time, sometimes by only a few months, sometimes by millennia. For example, Wright illuminates the modern challenges of the Sinai Peninsula by taking us back to the very origins of religious history in the region: “At the outset of the Camp David summit,” he writes, “Sinai had seemed to be the issue most easily resolved, but Carter would come to the conclusion that it was, in fact, the most difficult of all. It was where the trouble all began.” Wright begins the next section, “The Bible and the Quran tell very similar stories about the origin of the conflict between the Egyptians and the Israelites” (Wright 84). And so it goes, back and forth through time, history, politics, and religion. Through it all, Wright is able to keep his various, massive, and at times overlapping chronologies organized by wrapping up historical interludes to return, chapter by chapter, to each of the thirteen days.

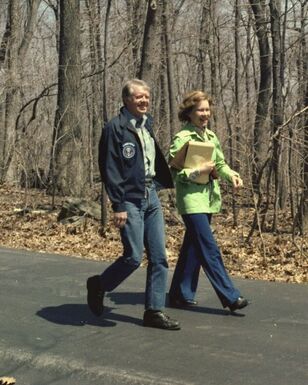

President and Mrs. Carter at Camp David (National Archives) President and Mrs. Carter at Camp David (National Archives) When I heard Wright speak about this book, he talked about the paramount importance of selecting characters for their character-worthiness, even if it meant not using a character. Since then I have been extremely critical of authors who forced a character out of someone who just… wasn’t. Early in his research for the book, Wright was in search of characters to liven the narrative. He traveled to Plains, Georgia to meet with Jimmy and Rosalynn Carter. During the interview, Rosalynn said something feisty and snappy to Jimmy. Wright was delighted and immediately thought, “There! There is one of my characters!” During the Camp David talks, Rosalynn had kept a journal, and she agreed to let Wright read through it. He was sent a stack of type-written papers, which he read in great detail, highlighting and making notes throughout. Some time later Wright received a phone call that Mrs. Carter would like her journal back as it was the only copy. “So that was an awkward conversation,” recalled Wright, who had assumed he had been given a photocopy of the journal and not the only copy. Nightmares of research gone awry aside, Wright knew just what sort of character Rosalynn would be. In his talk, he mentioned that he always searches for three kinds of characters: leading characters, supporting characters, and “donkeys”—those who carry the reader on their backs and lead them into the world of the book. Donkeys do not need to be main characters, they do not need to be likable, but they need to bridge the reader’s world and the world of the book. They need to be characters the reader can understand and even relate to so they can most effectively transport us into the narrative. The more effective the donkey, the more effective the book. In Thirteen Days in September, Wright uses Mrs. Carter as a donkey. It is mentioned several times that she spent a few days of the retreat attending other events, often in Washington. She would then return to Camp David (bringing the reader with her) to find the President and others in various moods, depending on how that day’s talks had gone. It was an effective way to give the reader a bit of an outsider’s perspective that then became an intimate observation, as Rosalynn herself shifted from not knowing how the day had gone to becoming her husband’s confidante. Her character also served to subconsciously remind the reader that Carter, Begin, and Sadat were secluded from the outside world. This would haunt Carter come re-election time, as he was criticized for being more concerned with peace in the Middle East than with the many problems plaguing Americans back home.  Lawrence Wright (Photo credit: Lauren Gerson, Wright at the LBJ Presidential Library in 2013, US National Archives) Lawrence Wright (Photo credit: Lauren Gerson, Wright at the LBJ Presidential Library in 2013, US National Archives) As Mrs. Carter came and went throughout the days, other characters came and went throughout the talks. Some days the negotiations focused more on Sadat, other days on Begin. The scene was always Camp David. It’s as if the story is a series of character entrances and exits, and each day is a new act. A play, perhaps? In fact, as Wright explains, the book did originate as a play. “This book had an unusual genesis,” he explains. In 2011, Wright received a call from President Carter’s former communications director, Gerald Rafshoon, asking if Wright would be interested in writing a play about the Camp David talks. The topic was a natural fit for Wright. He had lived in Georgia while Carter was governor and during his run for the presidency and in Cairo when Sadat became president. Wright had also spent a lot of time in Israel throughout his career as a journalist. His previous book, The Looming Tower, had prepared him well to tackle the great and complex religious, political, and social histories of embittered Middle Eastern countries and their relations to the United States. “Naturally,” he said, “the project appealed to me.” So Wright wrote the play, which was presented in 2014 at the Arena Stage in Washington D.C. But he soon realized, “I wasn’t finished with Camp David. There was much more story and there were many more interesting characters than could be fitted into a ninety-minute stage play.” And the play became a book (Wright 289). Wright’s organization of the three layers of Middle Eastern history allowed him to tell a much richer and more important story than the summit itself—as merely a chronicle of the talks themselves—would have been. Time Magazine political columnist Joe Klein shares my view in his 2014 review of the book for The New York Times: “Perhaps the greatest service rendered by Thirteen Days in September is the gift of context. In his minute-by-minute account of the talks Wright intersperses a concise history of Egyptian-Israeli relations dating from the story of Exodus. Even more important is Wright’s understanding that Sadat, Begin and Carter were not just political leaders, but exemplars of the Holy Land’s three internecine religious traditions.”

Not everyone agrees. In another review, written for The Wall Street Journal, conservative political advisor Elliott Abrams views Wrights’s “context” as superfluous and distracting from what he feels should be a chronicle of the peace talks and nothing more: “Mr. Wright calls the book both ‘a work of history and a work of journalism,’ and its shortcomings reflect that combination. The flow of the narrative about the summit… is repeatedly interrupted when Mr. Wright decides to tell stories from the Bible or give a brief history of Israel. These interludes feel like filler.” I believe that Abrams missed the entire purpose of the book and the multilayer structure of the narrative, not to mention the fundamental importance of religion as the basis for problems in the Middle East. I would have been foolhardy and narrow-minded to try to tell the story of the peace summit without telling the recent and ancient histories of the region and its religions. After all, context is key to the conflict and the ongoing struggle for peace.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

August 2020

Categories |

Proudly powered by Weebly