|

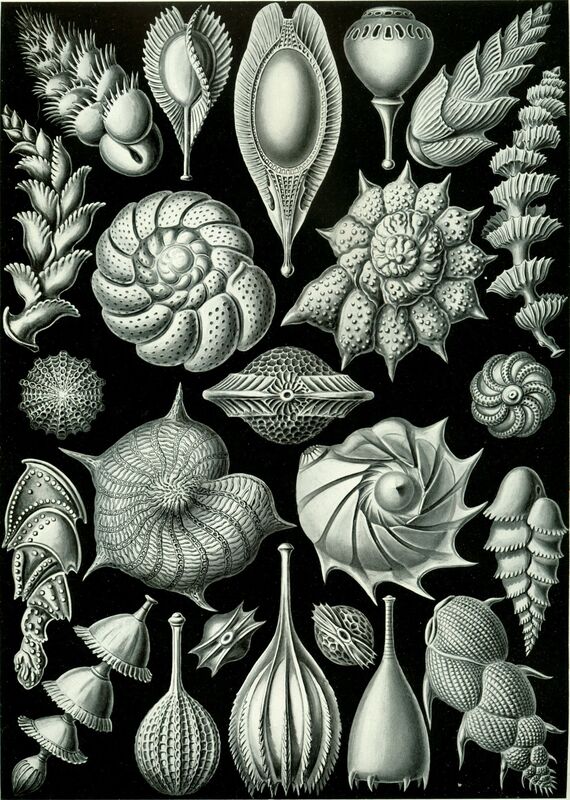

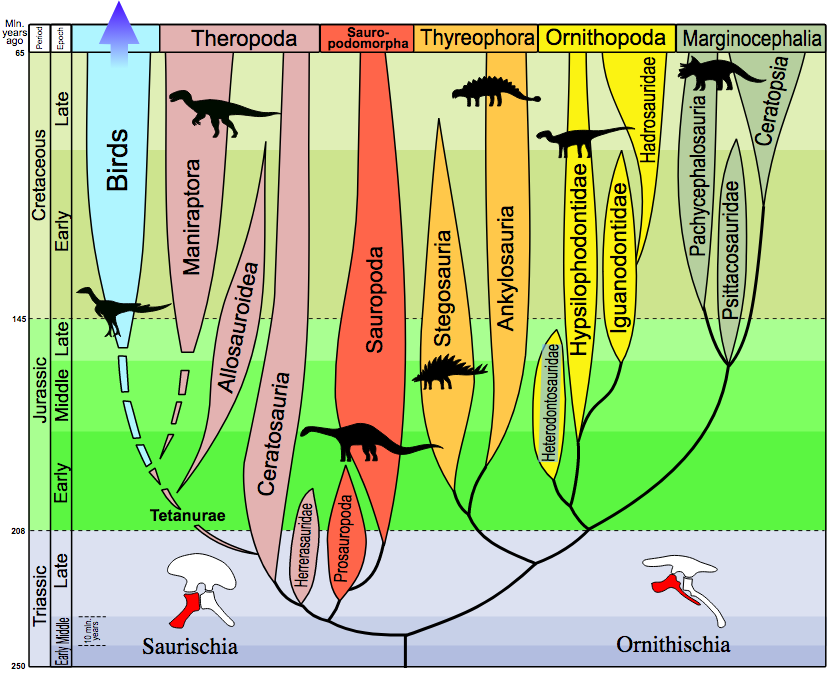

My kids love to watch "Elmo’s World." In one of their favorite episodes a little girl visits the American Museum of Natural History to look at the dinosaurs. She explains that "scientists called 'paleontologists' dig up the fossils of dinosaur bones and they put together skeletons which show how big they were!" The little girl plays with a toy skeleton, which she puts together "just like PALEONTOLOGISTS do!" She grins up to her mom, "Maybe I’ll be a paleontologist someday!" Fuzzy red Elmo comes back to wonder, "Where can Elmo learn more about paleontologists?" Why, the Dinosaur Channel of course! I let my kids watch cartoons while I cook dinner, and this was the point in the episode when one day I let the food sizzle and popped my head into their field of vision. "Did you know I was—am—a paleontologist?" I asked. Oh the look of confused disenchantment on their sweet little faces! Paleontologists are supposed to be cool and exciting and amazing, but I’m just… their mom! "Did you study dinosaurs?" Marie asked. "Nope, I studied tiny little animals that live in the ocean, so small you need a microscope to see them! They’re called foraminifera. Can you say that?" "For. A. Min. If. Era," three little voices dutifully piped back. Unimpressed, they asked me to turn Elmo back on. But the information must have settled somewhere in Marie’s brain because a few weeks later she asked me what the little animals were called, the ones that lived in the ocean and you needed a periscope to see. "Microscope?" "Yes. What are they called?" "Foraminifera. But we call them forams for short." "Did they also die at the same time as the dinosaurs?" "Well, some did. Some died a long time before the dinosaurs, and some are still around." "Mommy, are there still some dinosaurs around?" This is the question I have been waiting for! For Christmas I got Nick a t-shirt that’s a riff on the classic monkey-to-man image, but this shirt shows evolution from a Tyrannosaurus Rex to a chicken. Yes it’s true: birds evolved from dinosaurs. Marie has always loved birds. When she was 18-months old and we still lived in San Francisco we went to the zoo almost every week. Our first stop was the aviary and she always asked to eat our lunch by the pelicans. We have a big bin full of Schleich animals. We started the collection when Marie was barely two, and the first ones we got were the birds. Later, I got her a child’s bird identification book, and later still the National Geographic Field Guide to the Birds of North America. I have piles of birds she’s drawn with her chunky markers and crayons on white printer paper—magpies, star finches, parrots, roseate spoonbills, and wood pigeons. I got her binoculars and we made a bird feeder out of a toilet roll and sunflower seeds. She got a stuffed robin and a little nest, and made papier-mâché robin eggs which she painted blue. She cried when she outgrew a dress that was covered in birds. So when she asked if there are still dinosaurs around, I couldn’t wait to tell her that all those birds that she loves so much, all the birds in the whole world, are dinosaurs!  I had recently read Steve Brusatte’s The Rise and Fall of the Dinosaurs: A New History of a Lost World, so I was a font of knowledge on all things dinosaur, impact-related extinction, and bird evolution. In a chapter titled "Dinosaurs take flight," Brusatte writes, "There is a dinosaur outside my window. I am watching it as a type this. Not a photo on a billboard, or a copy of a skeleton from a museum, or one of those obnoxious animatronic things you see in amusement parks. A real, honest-to-goodness, living, breathing, moving dinosaur" (Brusatte 268). He is talking about a bird. The more you think about the way a bird cocks its head, the way its beady eyes glint, or the way its gawky neck juts forward and back, the more a bird starts to look like the dinosaur it really is. The bluejay flitting across our fence, the hawk soaring high about the hill behind our house, and the crows perched on our power lines all share the same common ancestor as Velociraptor and Stegosaurus. As Brusatte says, "That makes them dinosaurs…. [Birds] are every bit as dinosaurian as T. rex, Brontosaurus, or Triceratops… Birds are simply a subgroup of dinosaurs, just like the tyrannosaurs or the sauropods—one of the many branches on the dinosaur family tree." (Brusatte p. 270) Birds are dinosaurs. "It’s a notion that’s so important, it bears repeating," says Brusatte. People will often argue: birds evolved from dinosaurs, but they themselves aren’t dinosaurs. How silly would that be? If birds were dinosaurs? The dinosaurs all went extinct! There aren’t any dinosaurs anymore! Brusatte explains, "Yes, it can be hard to get your head around. I often get people who try to argue with me: sure, birds might have evolved from dinosaurs, they say, but they are so different from T. rex, Brontosaurus, and the other familiar dinosaurs that we shouldn’t classify them in the same group. They’re small, they have feathers, they can fly—we shouldn’t call them dinosaurs." (Brusatte p. 270-271) But Tyrannosaurs Rex is so different from Brontosaurus, and a penguin is so different from an eagle, that the visible differences between various orders, genera, and species hardly seems a solid argument. Perhaps what is more confusing and disconcerting is that the dinosaurs lived so very long ago that they couldn’t possibly still be around. And besides, they all went extinct. It is true that most of the dinosaurs went extinct 66 million years ago, when an asteroid smacked into the Yucatán Peninsula, causing the end-Cretaceous mass extinction—but a very few survived. Those went on to become the birds we know today. Sixty-six million years may seem like an incredibly long time, but it is no more than a sigh in the geologic history of the earth. In fact, today we live much closer to the age of Tyrannosaurus Rex than T. Rex lived to earliest dinosaurs, which first roamed the supercontinent Pangea during the early Triassic (252-247 years ago, and more than 160 million years before T. Rex). Today, more than ten-thousand species of dinosaur live among us, some of which we idolize, some of which we have domesticated, some of which we eat, and some of which we consider pests. That birds evolved from dinosaurs was first considered not long after Darwin published On The Origin of Species in 1859, but it wasn’t until the mid-to-late twentieth century that the theory became widely accepted among paleontologists. By the late 1980s, most paleontologists were convinced that many "birdlike" features, such as their long straight legs, three main toes, wishbone, and s-shaped neck, first evolved over the course of millions of years in dinosaurs. Brusatte describes these ancestors of birds as "upright, wishboned, bobbing-necked therapods [that] started to fold their arms against the body, probably to protect [their] delicate quill-pen feathers" (Brusatte p. 286). These dinosaurs, the precursors of today’s birds, were cousins of the famous Velociraptor. (Try to imagine a Velociraptor overlaid with an ostrich, and you’ll get the idea.) In addition to the physiological similarities evident in the skeletons of dinosaurs and birds, there are also behavioral similarities. Dinosaurs built nests and even cared for their young, just like birds do. But the most compelling evidence is that dinosaurs had feathers. In 1861, a 150-million-year-old fossil was found in Solnhofen, Germany, halfway between Nuremberg and Munich. A quarry worker split open a sheet of limestone and found a creature like no other ever seen before: a little smaller than a raven, it had a wishbone, feathers and wings like a bird, and sharp teeth and claws like a reptile. This creature, called Archaeopteryx, truly seemed half-reptile, half-bird. When I was in fifth grade, we had to do weekly "who, what, where, when" reports. We had to answer each of those questions about a newsworthy topic of our choosing. For reasons I no longer remember, one week I chose Archaeopteryx (a different week I chose the story of a baby born on an airplane, so not all my selections predicted a future as a historian of science). In my report I explained that Archaeopteryx is the oldest known bird in the fossil record and that this feather-covered, wishboned, toothy, tailed creature first inspired the notion that birds evolved from dinosaurs. "Can you imagine if a chicken had sharp teeth and a long tail?" I asked Marie. She giggled. Earlier that day we’d visited a farm and a chicken had pecked at her purple sparkly shoes. "Can you imagine if a Velociraptor had feathers and wings?" "No!" "Well, there once was a creature that looked a little like a feathered, winged Velociraptor and also a little like a toothed, tailed chicken!" "Where did it go?" "It went extinct a long time ago, but other creatures like it lived on and eventually became the birds we see today." When Archaeopteryx was first discovered in the 1860s, dinosaur paleontology was still in its nascent stage. Even though this half-bird half-reptile certainly looked like an early bird, the thing holding people back from also considering it a late dinosaur was that it was covered in feathers. If Archaeopteryx really was a missing link between dinosaurs and birds, that meant that feathers must have evolved at some point before Archaeopteryx. But dinosaurs were imagined as drab scaled creatures and the very notion that they might have had feathers (or even been colorful!) seemed preposterous. The main problem was a lack of fossil evidence. In paleontology, the axiom “absence of evidence is not evidence of absence” is a very real phenomenon. Soft body parts, like skin, muscle, organs, and feathers, are rarely preserved in the fossil record (Archaeopteryx was a very rare find). But at last, during the the 1990s, a holy grail of dinosaur paleontology was finally discovered: a feathered dinosaur. A rash of paleontologists descended on the Liaoning region of northeastern China, where a dinosaur called Sinosauropteryx had been found. This fossil showed a small dinosaur surrounded by a stunningly preserved fluff of feathers. Soon, lots of other feathered dinosaurs were found nearby, of more than twenty species. These fossils were “preserved Pompeii-style” when their world was buried repeatedly by multiple volcanic eruptions during the Early Cretaceous, between 110 and 140 million years ago (Brusatte 280). So: if birds have feathers, and the feathered Archaeopteryx is the oldest known bird, and the Lioaning dinosaurs proved that feathers evolved in dinosaurs, then it isn't hard to flip the logic around: feathers (among other features) evolved in dinosaurs, over millions of years dinosaurs evolved into a feathered creature that looked half like a reptile and half like a bird, and a creature similar to that, in turn, evolved into birds. The only way this is possible is if a group of feathered dinosaurs survived the end-Cretaceous mass extinction.  Some of our favorite bedtime stories are the How Do Dinosaurs… books by Jane Yolen, illustrated by Mark Teague. In these books, the various dinosaurs depicted model bad and good preschooler behavior. I pulled one of the books off our shelf and Marie and I flipped through the pages, eagerly pointing every time we found a feather. No longer the drab, dumb, scaley, crocodilian reptile of my childhood, the dinosaurs my kids love are bright and colorful, feathered, quick-witted, bird-like, and evolutionarily successful. I had planned chicken for dinner. I didn’t know if it would be exciting or traumatizing for her, but it’s all I had, so chicken it would be. The day went on and she drew more birds. That night at dinner she picked up her drumstick and said, “Daddy! We’re eating dinosaur tonight!” Steve Brusatte, The Rise and Fall of the Dinosaurs: A New History of a Lost World (New York: William Morrow, 2018).

2 Comments

Francisco Ramírez

2/10/2020 01:28:36 pm

Very well done, Dr. Lind.

Reply

Steve Wang

7/7/2021 03:30:04 pm

Wonderful essay! I love how you incorporate your personal story into an informative piece.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

August 2020

Categories |

Proudly powered by Weebly